Why did I start working with puppets? It's something that is within you. I never thought of going onto stage but it did come to me fairly quickly. I started off by working at a puppet theatre in Chiswick and the people working there: the woman was a wonderful operator and her husband a sculptor who was a brilliant puppet maker and I never worked such excellent puppets like that ever before or since.

The woman gave me a puppet and said "I give you a fortnight to work with it. I'm not going to tell you what to do with it, except how to hold it. Just work it". That's what I did. Without knowing how to operate it. But it set you thinking about how you do things yourself. How do you walk, sit down, take up things. How do you do it? How can I have the puppet do it the same way?

So you got a puppet control here. The idea is that its backbone carries the puppet and by tipping it about you get movement on the figure: forward or sideways. There are two bars perpendicular to each other and attached to the control for the 3 headstrings. Two of these are attached to the back of the head and one at the front. With these the head can nod or turn. And there are the eye strings. By putting one of your fingers though one of the two holes and rotating the bar (counter)clockwise the eyes move to the left or to the right. Which hand holds the backbone depends on whether you are lefthanded or righthanded.

I always tell people not to grab the control, but keep it very loosely, to hang it from your hand. You do need a flexible wrist. If you would grip the control rather than hanging it from your hand, it's very difficult to walk the puppet which is what you do with your free hand holding the two bars for the legs and hands. For most of the puppeteers, this is what their hands are like when the hold the controls.

The hand bar has a number of holes in it. This is because every puppet is different - even if they are replicates. When you string them up (in near darkness) you use one of the holes. I always found that if you have the leg strings closer together, you get a better walk. With more holes, you have some options. If it doesn't work, you use another hole. We never used or strung the leg strings if the puppet would not need to walk, because it might be hanging in front the puppet's face. I'm lefthanded and walking a puppet to the left is easier because your right hand manipulates the leg strings while your left hand carries the puppet. Walking the other way is almost impossible.

There is another bar across for the shoulders. Those too were not used to much. You would have much more broader action for a stage puppet that people watch from a distance, than you would for a film puppet. The idea being, that you have this bar here and the other bar there and the backbone. If you tip this forward, the head goes down, the shoulder would take the weight. And if you tip it further then the back one would take the weight, so you get a proper bow.

Mostly we got by by using the hands, head and eye strings. To fall down or to show the beginning of a movement of getting up so we also always also have a back string. But we dispensed of the shoulder bar most of the time. Only the beginning would be shown, then a film cut would suggest the rest. Time was an important element and determined whether or not we would remove strings not really needed for the scene.

Now about sitting a puppet. You don't just "flop back". When you are going to sit, you bend your knees and then sit down gracefully. And on getting up you have to pull yourself up. So it looks like there is a little bit of strength at the back of it. And all of the movements: you have to think about what you would do yourself to avoid it to make it look too puppet-like. It's the same with the hands. When we had wooden hands we carved them in such a way that we had a semblance of a point. With the more flexible and bendable hands used in Thunderbirds, it was much easier. They could be bended primarily to hold a gun or something else. And they too could point. It was much easier.

Most of the facial expressions was pure imagination. You hear the dialogue and you worked at the dialog and you moved the eyes, since the mouth was controlled remotely and you could not influence that. But you could turn the eyes away and back again. Sometimes when you did that the director would shout at you "Christine you lost the eye line", so you had to be careful, but you could do it. And imagination made it look like the whole face was moving.

If the shots were close enough, a puppeteer on the floor would hold the arm and move it rather than moving it from above. Pulling the hand strings would give quite a strong movement on the lower arm but little or none from the shoulder which looks unrealistic.

Moving the puppet is not easy. You're 8 feet above it on the bridge. So you move the control and the strings start to twist. And if the mouth control wires touch they short-circuit. There is a slight delay in the movement on those long strings. You turn it on the bridge and it looks wrong because the strings are turning from the top down to the bottom before the head starts to turn.

Replacing the head was easy. There is a screw that you tighten in the back of the puppet body or sometimes at the shoulder. The neck mechanism would drop into a bracket and then a screw would tighten it. So it's a question of undoing the costume and screwing the bottom part off. You would keep the body. You would take off the head and eye strings, but all others would remain in place: the hands, shoulder and leg strings. They were on different control bars so you replaced the head bars. The girl, Judith Shutt or Rowena or whoever we got, would just bring a holder with the other head.

Questions from the room:

How long did you work these puppets on the bridge without a break because those puppets are quite heavy?

Oh, for hours. Time was no object. We started with the strings during Torchy and Twizzle. We'd have to hold the puppet while they were lighting the scene. We did not have anything to hold on to on the bridge. So they made these wire rods that went along the front of the bridge. We had some cleats, some strings that we could lengthen, a bit of string in a loop at the end so we could hang the puppet on that loop and then lengthen or shorten the string. But hanging the puppet like that, you ran a risk that it wasn't always in the correct position for a scene. If it was back a bit and they could not light the face properly, we did have to be there and we would push it forward a bit but at least we did not have to lift the weight of the puppet all the time.

Then we started rehearsing. For some reason or other this spot that they lit changed sometimes. "It isn't in the right spot," they would say. "But that's where the hook is. That's where the puppet was." - "Well, it's changed you see. Can you put it a little bit forward? A little further... further". We had a leaning rail along the bridge against which we leaned more and more forward. "Are we going fairly soon?' "Yeah any minute now". But then the camera would be out of focus, then the focus changed. "Yeah, Christine doesn't mind going up trees". "No, she's not claustrophobic" even if I was, but we all did it and came through it.

So sometimes it was only a few minutes, but sometimes a lot longer. But it was OK - we were young.

How did you operate the underneath puppets and how do they compare?

This is much later - not until Captain Scarlet I think. It wasn't for the benefit of the puppeteers that they started to use this method! It was because of the glass or perspex canopy of the aircraft. For a puppet to sit in a craft there has got to be room for the strings to go through. Because of this hole in the perspex, the camera movement would be limited. Also if you would tip the head of the puppet, the string might touch the edge of the hole. So we operated from below. No problem there. The hands would be fixed on the wheel while someone at the front would turn the wheel. And you would keep the puppet alive: move the eye, turn the head a bit. But there wasn't a lot to do. It made it easier for us.

Is that Scott puppet from an original mould?

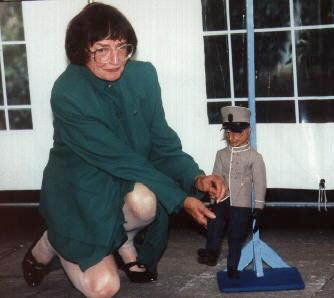

Yes. A man named Somebody Scott who has a memorabilia shop in Reading has got the plaster casts of several heads. We needed Scott for the Kit Kat commercial and without a reference I thought I might have to make a new one, which is always a bit hazardous because you never get it really right. So I was relieved when he turned up and let Richard Gregory make a cast from this. I made the original Scott and I recreated this copy, so I think it is the next best thing. He has original hands but none of the costumes are original.

Titan from Stingray here, is a resculped one. Because of a commercial we had to recreate it. It's not bad and we had to do it quickly but an original, unlike Scott, hasn't turned up. This Titan looks a bit more beneign, not as vicious as the real one. It's something in the mouth but I'm afraid to alter it so I think I'll leave it the way it is.

Barry Davis from Wales made Scott's body. I think he is one of the best body makers of the moment. They work so beautifully, they're nicely balanced. Unlike this Parker puppet here, which is Gerry Anderson's Parker. It is all original except for the costume. In the old days when fibreglass was new, we did not know how strong it was. So we did not want any accidents during the shooting and therefore we made sure they were strong and in the process we made it far too thick. The head and the body weighs a ton and that's why they don't work as well as Barry's new ones.

Especially walking those heavy puppets was bad. It looks bad on film. You had to lift the puppet to move it along. You would notice the space between the floor and the feet. And there is that slight unsteadiness.

Things come to you when you're talking. I just remembered: a lot of people, experienced well known stage puppeteers, walk their puppets as if it is sitting down: the feet slightly ahead of the puppet. No one has ever been able to do a perfect puppet walk. There is too much involved in the movement. You cannot do it with only two strings on the knees. If you walk, you normally smash your heel down and the rest of the body follows. You don't lift your leg up, you throw it forward like this. (Christine shows how, by holding the leg strings a bit in front of Scott, she can actually lift his leg in a straight way and then put it on the floor, and then lets the rest of the body follow. The walk looks a lot more convincing this way). I've told loads of people and young ones, but nobody seems to have gone off and do it like that.

How do you lift a cup of tea with a puppet?

I don't think you do that with a puppet because you cannot do any swallowing or things like that. But I'll tell you how we do a puppet that gets a gun out and shoots somebody. Will that do?

You would rig the puppet so that the hand would be near the gun. Then you would cut the filming. You would fix the gun to the hand. You would cut to the fellow he's going to shoot. Meanwhile you would put a string through the elbow so you have a string through the elbow and the hand so that you can lift the arm to a straight arm. And then the gun would be rigged with an explosive and you would shoot. Cut and show the fellow going down. Then you cut for a bit of blood on the guys clothes. It's all trickery really.

When Virgil slides into the cockpit of Thunderbird 2 and pulls this lever for the lights, how's that done?

We all had a laugh on this. He's sliding down this thing and landing in this cockpit is quite uncomfortable compared to simply sitting. We would fix the hand to the lever and somebody underneath would operate the lever. And then he has three seconds to change from his casual cloths into this uniform. All a bit silly really. All these outrageous, brilliant uniforms, just to be secret.

This is all I can tell about operating the puppets. I've got some more bits and pieces. I got some string here - these 8 foot strings. These display puppets here use nylon but at the time it was this wire. We found that the nylon wires stretched under the 5 to 8 pounds weight of the puppets. So we used metal wires from Ormiston. It was treated so that it took the shine off the wire and it also took the current.

The wires go down from the plug on the control to where the strings enter the heads to the solenoids. When the solenoid was activated, the steel plate inside the head would come up and open the lip attached to it. So you plugged in some wires on the control that would eventually go to the lipsync tape recorder. Pulses from here would then open the mouth. We did not have to worry about the dialog. Before the lipsync mechanism we opened the mouth with our thumbs. It was not the learning of the dialogue that was the problem but the spaces between the sentences. We tried to get to open the mouth at the beginning of the next sentence and that was virtually impossible. And it was the editors that said "We need to do something about it. Gerry, what do you want: sync the dialogue to the beginning of the sentence or the end?" So instead Gerry devised the lipsync mechanism and had somebody else to make it. It was a godsend to us because we could then concentrate on the action of the head and the puppet rather than wondering when the dialogue was going to come in and have your thumbs at the ready. So that made a lot of difference.

How do you string up the heads for this purpose?

The solenoid is inside the head. So you would thread the two wires through the holes in the back of the head and you tie them with little washers at the end of the wire. The hair would cover up the holes. We don't use solenoids anymore for modern puppets: those are radio controlled. But in those days, we had these metal bridges with a wooden leaning rail. On a hot day you had sweaty hands. And you were holding your puppet and you were ready for a rehearsal. And by accident you would touch the metal bridge. By God, would that give you a kick! "Oh girl," they would say, "it's alright - it'll make you live ten minutes longer!" It was quite a high voltage - 50 Volts or more. Possibly because of the resistance of the wires themselves. You knew which of the two wires not to touch normally because they were live. From the controls, heavier cabling would then run to the tape recorder.

I also brought my toolbox along. I used to have a chatelaine. It was a dog's lease hanging around my waist with holes drilled in it. All sorts of things were hanging on it. My scissors, plyers, tweezers, forceps. All people working in animatronics have scissors. You would put it down. Next thing the set dressers would come round and cleared everything off the set. That was goodbye to your scissors. So that's why I started to have them on me. Needles were also used of course - of different sizes. You got a fairly big needle to string a leg string. You got this hole in the front of the leg, so you had to find this hole through the clothes of the puppet. And the director kept shouting "Are you ready Christine?" - "Yeah, in a minute". But sometimes it was difficult to find the hole. Once you got it, you pushed the needle out with the wire threaded through it, right the way through to the back. So you hold that, take the needle off and you have now a wire with a hook at the end. Keeping hold of the bit of wire at this side, you poke up this hook the back of the trouser leg and you ease it down so the wire comes out the the back of the heel. You put the wire along that slot there and squeeze it together with these fishermans pellets and that traps the wire. It always worked well.

Although miniskirts were quite the thing to wear at the time, none of our girl puppets could wear them because of these jointed knees. You had to be careful about the position where the knee wire would go through the skirts because otherwise the skirt would make funny movements when the wire is pulled.

The head and the eye strings were the worst though. Especially with the girls. It took a long time and the directors were always in a hurry. The heads were marked, but if you did not put the wires through at the exact marked places, the wigs would move. Everytime you restring a puppet, you had to take the wig off and mark it where the wires go through. It must then be restuck, recombed - that was a long job. Any of the girls. The men were easier: their hair was stuck on. It was just a matter of combing it. We had this spray, anti-flare, we used when the wires still shone when the lights were very bright. We used puffers for this. The floor puppeteers could work on those strings for half an hour. They were very patient. If it didn't work they would use a different colour. The anti-flare is slightly sticky on the wire. The fact people today still see the wires is not because we did a bad job, but the definition of the modern television is much better. On the sets in the past, you could not.

This concluded the workshop by Christine Glanville because the next group needed to start. Giving it her way, she would continue for much and much longer.

Transcript and photos courtesy of Theo de Klerk. For more on this convention, see Theo's report on Fanderson Gold 96.